Sep 17, 2020

Grids

I studied painting at Kingston School of Art from 2001 to 2004. Much of my output from that time involved grids, and I see this work as a thinking-out-loud exercise, a personal investigation into what it is to make images and what it is to view them.

“these products are really just records, documents, outgrowths of this process of becoming conscious”

Joseph Beuys

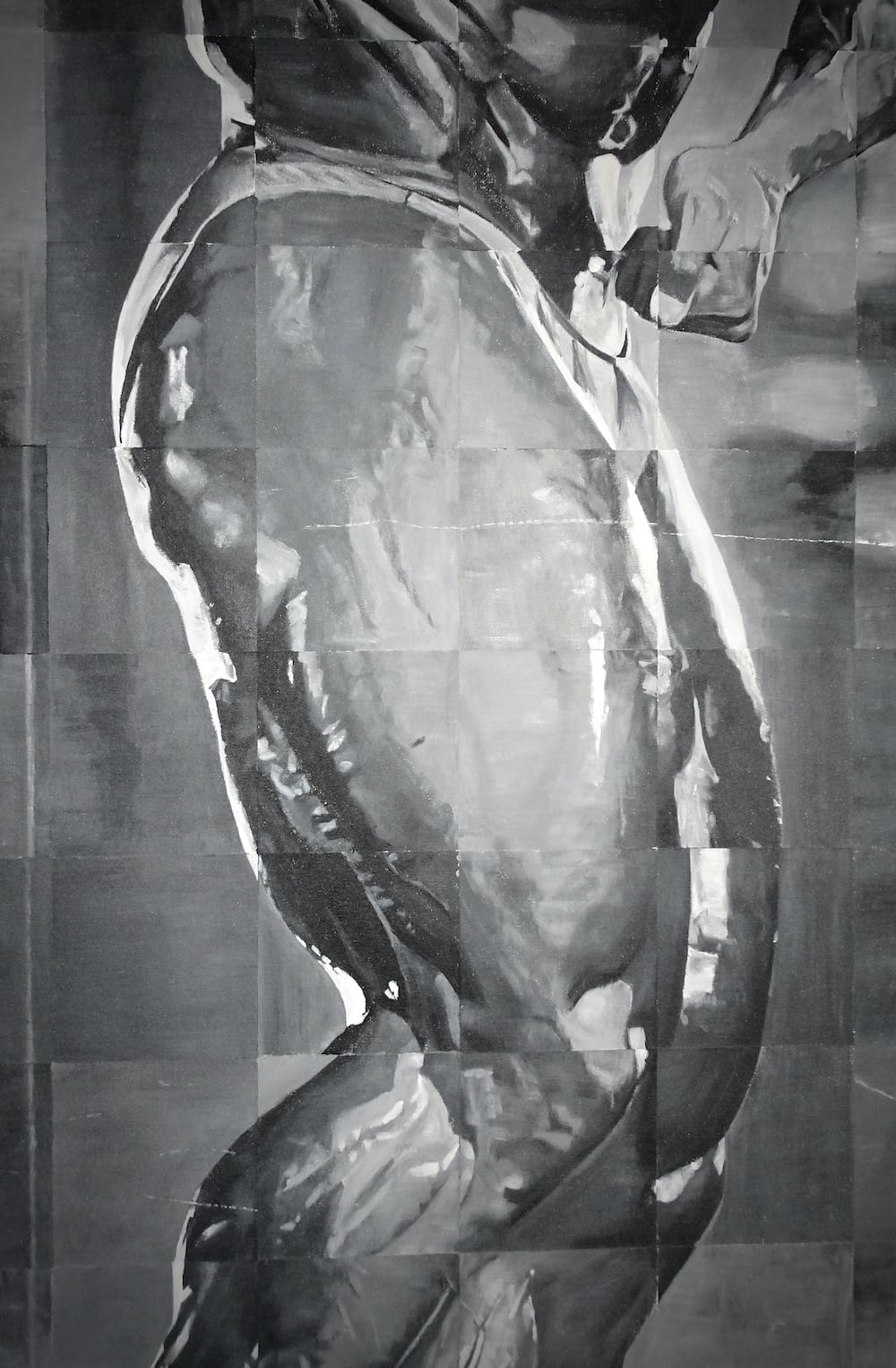

Each square in my grid paintings is chosen at random, executed in total isolation from its surrounding squares, and is worked on up to a common time limit. I felt that to zero in on one component at a time was, paradoxically, to defer to the primacy of the canvas as a whole, as no constituent part gets unequal attention despite what information it might contain. I liked the democracy of this, an explicit reminder to me that every square inch of a picture is essential to its overall composition and effect.

The result is a fractured mosaic of flawed, mismatching pieces, which only resolves into a ‘satisfactory’ image when viewed at a distance. The surface is animated as one approaches from a distance and signal becomes noise, and as one’s eye travels across the painting. This discord sets up a destabilised and reciprocal relationship between viewer and artwork.

When the viewer inspects the canvas at close range, they may make their own value judgment by picking out a favourite square, a particularly pleasing unit of the whole. I like that this arises from my treating each square as an entirely independent entity in an attempt to remove such value judgements during the work’s creation.

I also like the way this primitive method of mechanical reproduction highlights my human fallibility. Squares jar against each other; in this way an image which at a glance might be described as photo-realistic, actually ‘demonstrates itself’, to paraphrase Richter. I’d hope that the viewer does not read a painting as an illusionistic quote from the real world, but instead conciously encounters it as its own thing, a physical fact in its own right.

I try to further emphasise surface by including imperfections in the source image such as scratches from the photocopier glass, or by painting the surface of water, which slows our eye as we can’t make an instant ‘read’. It’s hard to identify a scale, our consumerist eye trained on instant visual signalling is frustrated when a referential ‘something’ refuses to emerge from marks of pigment.

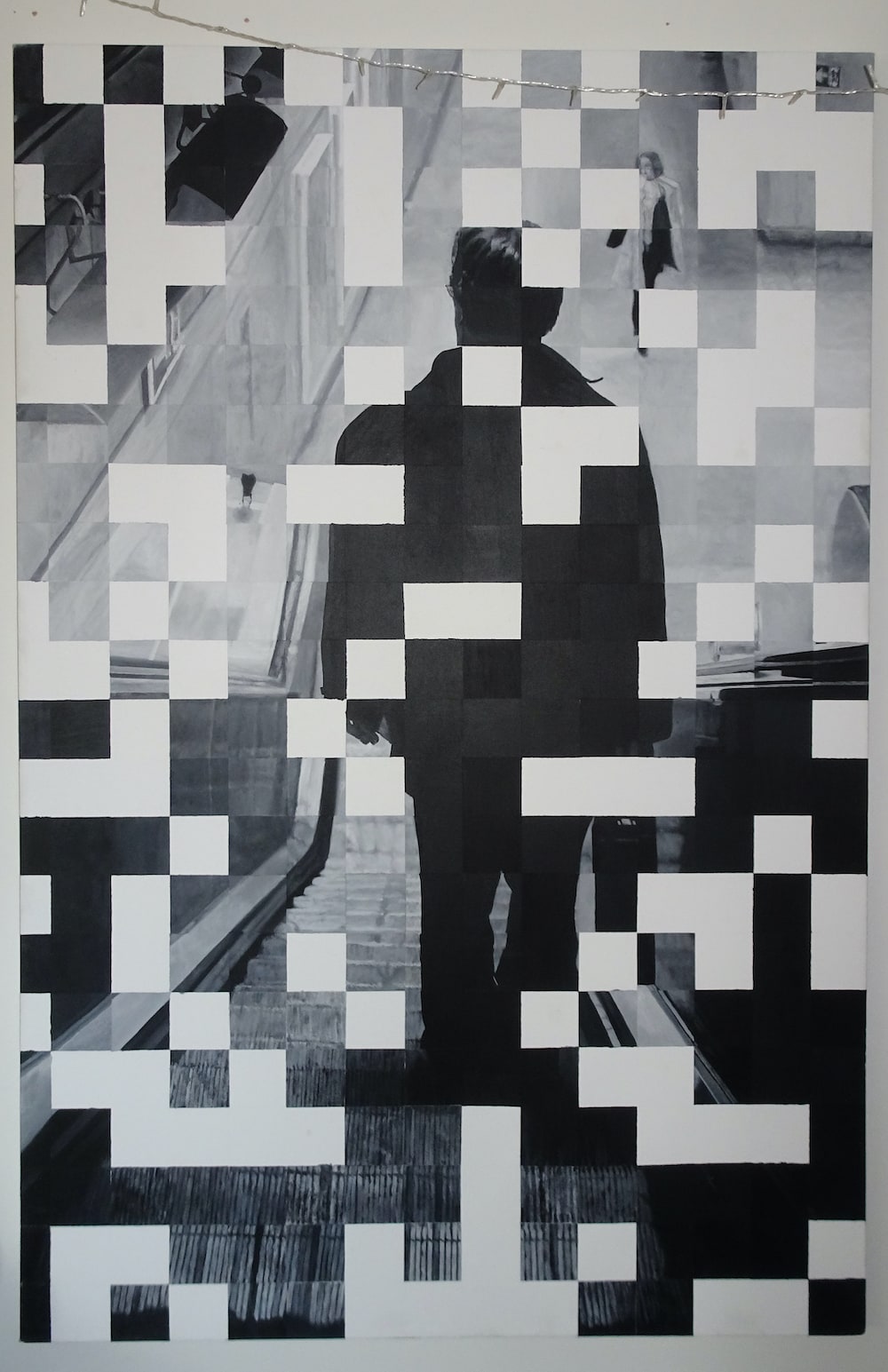

Or I simply leave some squares blank. Ironically, this heightens the illusion of three dimensional space ‘behind’ the white picture-plane. Further emphasis here on the substantiveness of the photograph itself which is the true subject matter, this flat analogue of the real world, with its distinctive depth-of-field effect which somehow signifies ‘truth’, or ‘reality’.

Blank squares seem like a breaking of some unwritten but obvious rule; the painting feels unfinished, unresolved. On reflecting about other ways to make ‘unfinished’ work, I wondered whether instead of making ‘less than one’, I could make more than one - a series of identical paintings might perhaps question the notion of completion. If the artist does not stop an artwork when it appears finished, then where is a resolution to be found? If there could be any number of the same thing, this subverts the idea of the art object as a kind of closed-loop, a unique entity, a thing with a singular authenticity.

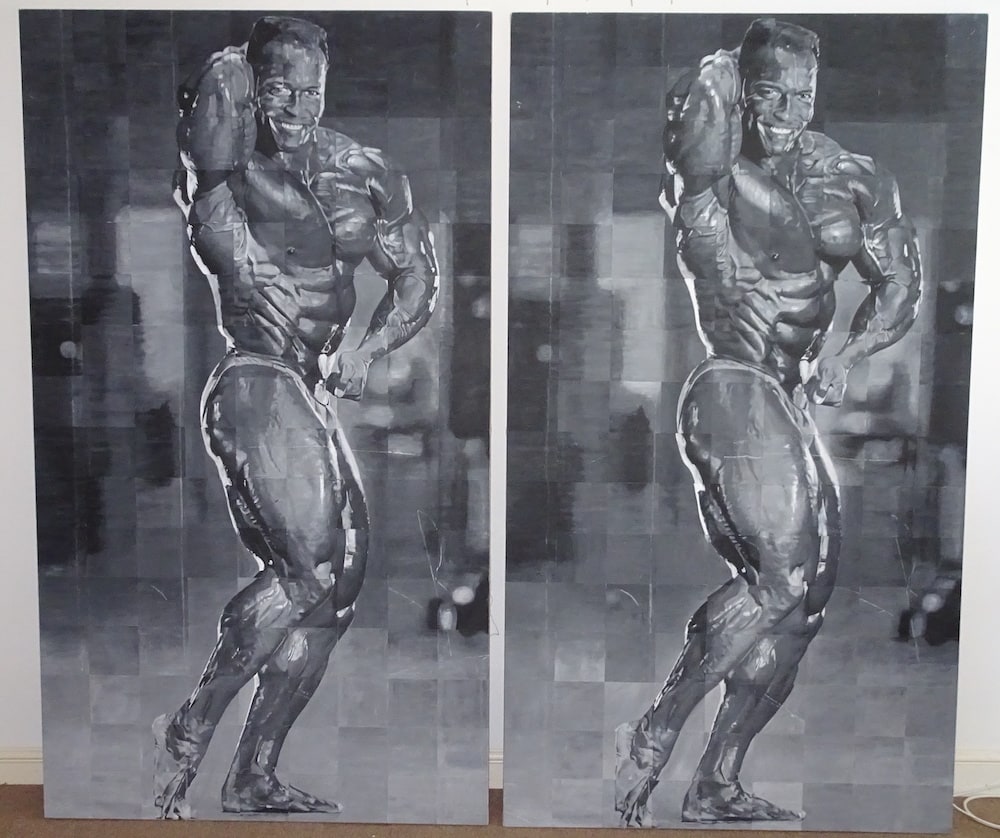

In ‘Reps’ I painted the same image of a bodybuilder twice. I painted them concurrently, jumping between the canvases at random so as to maintain that democratic approach outlined earlier - if I did one to completion and then another, would the second be executed less ‘accurately’ because of waning interest and energy, or more accurately because of the practice I’d had? But it looks like a process of sequential duplication is going on within the work itself, not just in relation to its subject matter.

And drawing attention to its subject matter is where I felt that Reps was successful. I’d felt that viewers were dismissing my bodybuilding imagery. I was not doing enough to make them question why I was doing it, to wonder what I saw there that prompted me to chose that subject over all others. The idea of repeating the same monumental figure across two canvases - two meticulous, labour intensive paintings - seemed to be a grand statement more apt to the grand statement that the bodybuilder himself makes. To paint a thing twice seemed to me to be saying, in unison with the figure, “I really mean it”.

In as succinct a nutshell as possible: the peculiar, totemic forms of bodybuilders are intended in this work to be emblematic of key qualities and postures that Art shares with bodybuilding subculture; transcendence, alchemy, industry, pathos, arcane beauty ideals, and the gaze.